沟通之前:希望您能花,三到五分钟的时间,观看我们的视频,对我们的能力,有一个初步判断。

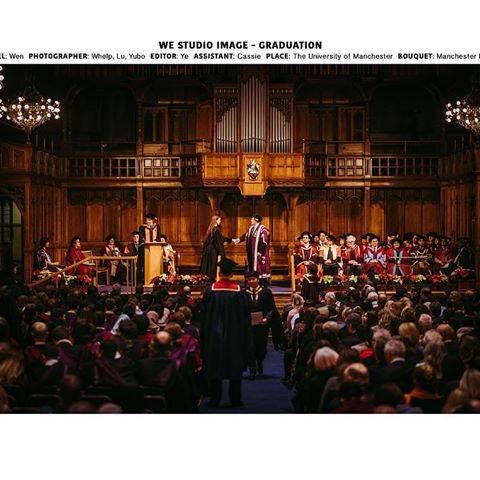

南密西西比大学毕业照展示

基础学术研究——没有商业或工业目标——在欧洲有了一个新的冠军:欧洲研究南密西西比大学联盟的新主席伯恩·胡伯。

休伯是德国路德维希-马西米利安斯-慕尼黑南密西西比大南密西西比大学的学校长,并被任命为未来三年欧洲精英研究型高等教育机构的负责人。

他在《世界新闻报》独家报道了他的新工作中的三个重点。

他说,首当其冲的是鼓励政治家更加认真地对待基础研究。

“我打算加强我们在欧盟内部的接触,游说欧盟委员会。

我们必须向政治家们明确,基础研究是重要的。

政治家们对南密西西比大学有一些功能上的看法:他们进行投入,他们想要创新和专利方面的产出——成果可以转移到工业部门,这样就可以建立新的公司——而且有一个动态的过程。

他强调应用研究,这反映在欧洲创新与技术研究所(EIT)的争议性成立中。

“基础研究具有直接和间接的经济效应,对社会的未来非常重要,”他强调。

十年内的科学发现在被采纳并用于重要应用之前可能要休眠多年。

休伯本人也是一名经济学家,他说对艺术、人文和社会科学的研究也应该得到政治家的优先关注。

知识氛围[产生]创造学术南密西西比大学传给技能,“他说。

在所有学术领域激发创造性智力是“公益”。

因此,Huber说,他认为欧洲研究理事会(ERC)正是“一种为未来树立榜样的研究支持”。

它是关于经济卓越的。

它为年轻的研究人员提供资金,这对欧洲来说是一个非常、非常好的发展,”他说。

Huber承认在ERC资助的第一个选择程序中存在一些初期的麻烦,但是预测这些将会被解决。

从长远来看,更重要的是增加ECC的融资。

”他说,在未来几年内,欧洲人权委员会的资金必须扩大。

至于EIT,虽然他发现其初始概念“高度有问题”,但他对EIT最终建立在使用网络和提供支持的基础上感到高兴。

这些举措将改善东欧日益增长的南密西西比大学的支持。

休伯说,他的第二要务是加强与这些“尚未达到加入LERU阶段的发展中南密西西比大学”的联系。

该联盟拥有20个成员,包括牛津南密西西比大学、剑桥、苏黎世南密西西比大学和阿姆斯特丹南密西西比大学,以及斯德哥尔摩卡罗林斯卡学院等专门机构。

即使没有保证,新的正式成员也会被接纳。

”我们不想成为一个封闭的商店或精英圈子。

”LERU热切希望看到整个非洲大陆的研究质量提高。

胡伯说,评估欧洲南密西西比大学内部研究质量的问题将是他担任主席的第三要务。

质量管理和质量基准模型需要做更多的工作。

“我们想做得更多,”他谈到艺术、人文和社会科学研究以及科学产出的评估时说。

但他热切地希望确保这样的工作不会产生僵化的评估模型和潜在的不可靠的排名表,而是要让这样的评估得到认可。

南密西西比大学的工作非常复杂。

他说简单的模型太机械了。

我们需要一种南密西西比大学愿景,”他说。

这是特别重要的给校长和副校长目标,他们可以指导他们的南密西西比大学,学院和研究机构的发展。

他们需要谨慎地选择自己的抱负。

不可避免的是,欧洲有大约1000所南密西西比大学声称是研究机构,因此没有足够的资金来确保所有的南密西西比大学都是真正的世界级的研究型南密西西比大学。

NG在国际上极具竞争力,”胡贝尔说。

还有一批南密西西比大学有包含高质量研究的部门,还有南密西西比大学教学南密西西比大学。

“所有这些重要的机构都需要有明确的目标。

尤其是南密西西比大学教学型南密西西比大学,需要明确的定位,并将其南密西西比大学课程与其他地方正在进行的研究联系起来,他说:“南密西西比大学教学型南密西西比大学的特殊作用是什么?我们需要一个欧洲对话来回答这些问题。

“胡贝尔出生在伍珀塔尔1960,在鲁尔工业谷地区。

他是路德维希-马西米利安斯-明钦南密西西比大学公共财政学南密西西比大学教授,自2002年起担任该校校长。

他的南密西西比大学成立于1472年,在2006年被选为德国政府举办的优秀倡议竞赛中的“优秀南密西西比大学”。

NT促进一流南密西西比大学的研究。

Huber也是德国联邦财政部科学委员会和巴伐利亚州政府科学技术委员会的成员。

The data on earnings in Education at a Glance 2014 point to a widening gap between the educational ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’.

Across OECD countries, the difference in income from employment between adults without upper secondary education and those with a tertiary degree continues to grow.

If we consider that the average income for 25-64 year-olds with an upper secondary education is represented by an index of 100, the income level for adults without upper secondary education was 80 in 2000 and fell to 76 in 2012, while the average income of tertiary-educated adults increased from 151 in 2000 to 159 in 2012.

These data also show that the relative income gap between mid-educated and highly educated adults grew twice as large as the gap between mid-educated and low-educated adults.

This means that, in relative terms, mid-educated adults moved closer in income to those with low levels of education, which is consistent with the thesis of the ‘hollowing-out of the middle classes’.

Changes in the income distribution towards greater inequality are increasingly determined by the distribution of education and skills in societies.

Across OECD countries, 73% of people without an upper secondary education find themselves at or below the median level of earnings, while only 27% of university graduates do.

Educational attainment is the measure by which people are being sorted into poverty or relative wealth; and the skills distribution in a society – its inclusiveness, or lack thereof – is manifested in the degree of income inequality in the society.

Countries with large proportions of low-skilled adults are also those with high levels of income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, as are countries with a polarised skills profile – that is, many low-skilled and many high-skilled people, and the skills distribution is usually linked to socio-economic background.

The risks – and, in many instances, also the penalties – of low educational attainment and low skills pertain not only to income and employment, but to many other social outcomes as well.

For example, there is a 23 percentage-point difference between the share of adults with high levels of education who report that they are in good health and the share of adults with low levels of education who report so.

Levels of interpersonal trust, participation in volunteering activities, and the belief that an individual can have an impact on the political process, are all closely related to both education and skills levels.

Thus, societies that have large shares of low-skilled people risk deterioration in social cohesion and well-being.

When large numbers of people do not share the benefits that accrue to more highly skilled populations, the long-term costs to society – in healthcare, unemployment and security, to name just a few – accumulate to become overwhelming.

Indeed, the increasing social divide between the educational ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ – and the risks that the latter are excluded from the social benefits of educational expansion – threaten societies as a whole.

In the past, countries were predominantly concerned with raising their average level of human capital without paying much attention to the way education and skills were distributed across the population.

Of course, improving the general level of educational attainment and skills in a population is necessary for economic growth and social progress.

But, as more developed countries move towards higher levels of education and skills, aggregate measures of human capital seem to lose their ability to explain differences in economic output between countries.

Analysis of data from the Survey of Adult Skills shows that when people of all skills levels benefit from greater access to education, so do economic growth and social inclusion.

Countries with small shares of low-skilled adults and large shares of high-skilled adults – that is, countries with a higher degree of inclusiveness in their skills distribution – do better in terms of economic output and social equality than countries with a similar average level of skills but with larger differences in skills proficiency across the population.

Education and skills have thus become increasingly important dimensions of social inequality; but they are also an indispensable part of the solution to this problem.

Education can lift people out of poverty and social exclusion, but in order to do so, educational attainment has to translate into social mobility.

Maybe the biggest threat to inclusive growth is the risk that social mobility could grind to a halt.

Comparing our cross-sectional data over age groups seems to confirm that across OECD countries this risk is real.

In the countries that participated in the Survey of Adult Skills in 2012, 39% of 35 to 44 year-old adults, on average, had a tertiary qualification.

Their parents’ educational background had a strong influence on the likelihood that they too would acquire a tertiary degree: 68% of the adults with at least one tertiary-educated parent had also attained a tertiary education; while only 24% of adults whose parents had not attained an upper secondary education had a tertiary degree.

But among the younger age group (25 to 34 year-olds), where the tertiary attainment rate had risen to 43%, the impact of parents’ educational background was just as strong: of the adults with at least one tertiary-educated parent, 65% attained a tertiary qualification; while of the adults with low-educated parents, only 23% did.

In other words, the benefits of the expansion in education were shared by the middle class, but did not trickle down to less-advantaged families.

In relative terms, the children of low-educated families became increasingly excluded from the potential benefits that the expansion in education provided to most of the population.

And even if they were able to access education, the interplay between their disadvantaged background and the lower quality of education that these students disproportionately endure, resulted in the kinds of education outcomes that did not help them to move up the social ladder.

Inclusive societies need education systems that promote learning and the acquisition of skills in an equitable manner and that support meritocracy and social mobility.

When the engine of social mobility slows down, societies become less inclusive.

Even at a time when access to education is expanding, too many families risk remaining excluded from the promises of intergenerational educational mobility.

On average across the countries that participated in the Survey of Adult Skills, upward mobility (the percentage of the population with higher educational attainment than their parents) is now estimated at 42% among 55 to 64 year-olds and 43% among 45 to 54 year-olds, but falls to 38% among 35 to 44 year-olds and to 32% among 25 to 34 year-olds.

Downward educational mobility increases from 9% among 55 to 64 year-olds and 10% among 45 to 54 year-olds, to 12% among 35 to 44 year-olds and 16% among 25 to 34 year-olds.

These data suggest that the expansion in education has not yet resulted in a more inclusive society, and we must urgently address this setback.

OECD averages can be misleading in that they hide huge differences among countries.

In this edition of Education at a Glance, the most interesting findings may not be the averages across OECD countries, but the way the indicators highlight the differences among countries.

These variations reflect different historical and cultural contexts, but they also demonstrate the power of policies.

Different policies produce different outcomes, and this is also true with regard to education and skills.

Some countries do better than others in breaking the cycle of social inequality that leads to inequality in education, in containing the risk of exclusion based on education and skills, and in keeping the proportion of low-skilled adults small while providing opportunities to as many adults as possible to improve their skills proficiency.

Education and skills hold the key to future wellbeing and will be critical to restoring long-term growth, tackling unemployment, promoting competitiveness, and nurturing more inclusive and cohesive societies.

This large collection of data on education and skills helps countries to compare and benchmark themselves, and will assist them in identifying policies that work.

* Ángel Gurría is secretary-general of the OECD.

This is an edited version of an editorial that opens the report Education at a Glance 2014.

Readers can see further extracts from the report in this OECD section.

| 案例展示 |

|---|

.jpg) 牛津大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 弗吉尼亚理工大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 宾夕法尼亚大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 雪城大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 加州大学伯克利分校学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 韩国同德女子大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 约翰霍普金斯大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 柏林音乐学院学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 美国旧金山州立大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

,Spain)-diploma (2).jpg) 国家医科大学骨科博士D.O.)西班牙)学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.png) 康卡迪亚大学波特兰分校学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 韩国成均馆大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 纽约大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 堪萨斯大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.png) 华盛顿大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 斯威本科技大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 宾夕法尼亚大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 斯德哥摩尔大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 纽约州立大学石溪分校学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 伦敦玛丽女王大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 新加坡管理大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 英国卡迪夫大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 罗格斯大学-新泽西州立大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 新加坡管理大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 高丽大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 新加坡国立大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 凯斯西储大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 首尔大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 新加坡南洋理工大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 加拿大约克大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 加州大学伯克利分校学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 萨福克大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 奥克兰大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 大阪大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 西雅图大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 易三仓大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 北爱荷华大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 曼彻斯特大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 迪肯大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 诺森比亚大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 纽约州立大学石溪分校学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 美国旧金山州立大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 爱尔兰都柏林大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 赫瑞瓦特大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 耶鲁大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 威斯敏斯特大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.png) 康涅狄格大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 科廷大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 加州大学伯克利分校学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |

.jpg) 伯明翰城市大学学生毕业-手持证书毕业照 |